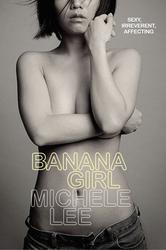

I never would have read Banana Girl if a friend hadn’t lent it to me. I almost never read memoirs, especially of people I’ve never heard of.

I never would have read Banana Girl if a friend hadn’t lent it to me. I almost never read memoirs, especially of people I’ve never heard of.

Michele Lee is a Melbourne-based playwright, about to embark on a six-month trip to Laos. Australian-born but the daughter of Hmong immigrants, Michele is a self-proclaimed ‘banana’.

Michele has a lot of sex, mostly of the detached, non-relationship kind. She details her meetings with guys like Mr Mercedes, who she has afternoon sex with in buildings he manages. She’s had a handful of serious relationships, the stories of their beginnings and endings floating through her tales of the present. Michele seems to still be friends with all of them to a certain degree, the implication being that once they break up she’s never so devastated that she can’t stay in touch. Yet, her memoir begins with her dalliance with New Zealander Jackie Winchester. Michele visits him in New Zealand and seems to fall for him rather quickly and completely. But it’s complicated.

All of Michele’s ex-boyfriends are given pseudonymic nicknames (I’m assuming to protect their identities while also being knowingly cutesy). Among them is the Cub (a much younger casual liaison), Husband (ex-serious-boyfriend, who she still works with, as well as being neighbours and friends), and Four Track (her second boyfriend from when she lived in Canberra).

I was a bit disappointed at the level of introspection. Deep down Michele knows that she often handles her significant relationships (including friendships) poorly, the conversations she includes that point the finger at her self-centred behaviour show that. She has a conversation with the Cub about her relationship history. Michele has just deleted the Backpacker (an ex living in London) from Facebook. The Cub says, ‘Don’t you think that’s, well, passive? Passive-aggressive?’ and, ‘So why would you delete him?’ She has no real response, just ‘But I was aiming for being assertive’ (despite being well aware that the Backpacker doesn’t know he’s been deleted) and, ‘I suppose I could just email the Backpacker and ask him what’s going on.’ (She hasn’t even tried the direct approach).

Michele also writes very funny imaginary letters from her fifteen year-old self; essentially the voice of her conscience, the voice of judgement – ‘You have sex with strange guys in empty buildings. What if he’s a rapist?’ Michele, through young Michele, knows the accusations that her friends and family are probably telepathically, if not actually, bombarding her with. So when accused, why doesn’t she defend herself. Because she has no idea why she behaves the way she does?

It would’ve been interesting to know why Michele thought she pursued all of these casual sexual relationships. Yes, it’s clear she enjoys sex but that’s not a real reason to have sex with three different guys in a week. I’m curious about the why. It seems strange, and possibly completely unfair, to be writing this about a real person, someone living right now. Maybe it’s the conversational tone, like a friend is telling you secrets, but sometimes you just want to shake said friend, to get them out of themselves, to get them to question their actions. And then other times you just sit and nod, allowing them to have their moment of self-pity, unencumbered by self-doubt or judgement.

I’m focusing too much on the sex, of which there is undoubtedly much. There’s also a bit thrown in about a previous trip to Laos. And the humorous side to the pain of being an artist – a sex farce play Michele writes that reviewers just don’t get, being a young playwright but only actually seeing plays that she can scrounge free tickets to. It was cool to read about Melbourne. Normally I like to read about people and places that have nothing to do with my own life but, living in Melbourne myself, it was enjoyable and kind of soothing to read about a life that has some sort of kinship with my own.

On the whole, Banana Girl is breezy and witty, yet I found it quite melancholy. The story of Michele in year eight feeling inadequate because her best friend, Pretty Polly, had lost her virginity the year before, leading to her downing kirsch on a ‘Friday night under the willow trees in Woden to try to accelerate [her] loss of virginity’ left me quite forlorn.

Michele Lee is undoubtedly funny and genuine. But despite the confessional style of the stories she tells (she bares the facts of her life for all to see) there’s a distance there. I hope she writes more books (I’m not really one for plays) because I can see her growing more comfortable and letting herself truly get close to her material.